What Is The Right Pricing Strategy

There are really only two pricing strategies:

- Low-cost leadership

- High-price differentiation

Everything else just falls somewhere in the middle.

The pricing strategies

In fact, most small businesses don’t have a pricing strategy. They often use what I call, emotional pricing; reacting to gut feel and emotion rather than the facts.

Reacting to what the competition is doing. Pricing based on guesswork, or simply pricing the way it’s always been done in the past.

Low-cost leadership

This is a strategy where you make a conscious choice to focus on low prices and undercut the competition. Your goal is to dominate your market with a low price. This can be an effective strategy and we see it executed in businesses such as Richer Sounds, Dell, Ryanair, IKEA, Aldi and Lidl.

The trouble is, you need the right set of circumstances for it to work.

It is very, very rare for this to be a sensible choice. To do this you must have something unique in your cost structure that means that you have lower costs preventing your competition copying your strategy.

So, let’s consider the alternative.

High value differentiation

If you don’t have scale or capital to dominate your market, you are much more likely to be successful by focussing on a high-margin product or service offering the customer added value. The key is to focus on differentiation and offering more value. Very often it makes sense to operate in an appropriate niche.

Think about Eddie’s business.

Perhaps his current pricing structure has been arrived at by copying his competitors. If instead he realises he has a particular area of expertise which is particularly valuable to some of his customers and he decides to pursue this as a niche, he adds some extra value by repackaging his services and puts his prices up by 25%. He wants to be positioned as the best videographer and now wants to be much more expensive than his competitors.

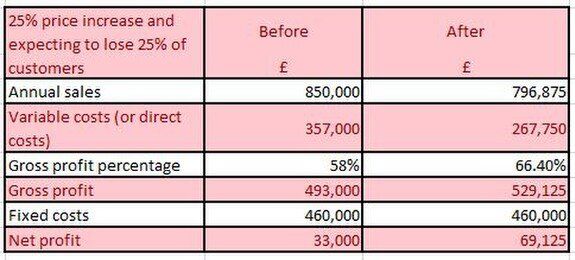

Eddie analyses his current customer base. He crunches the numbers. He realises from talking to his customers that one category who make up 75% of his sales will value the direction he is going in and the extra value he will add. And 25% are likely to leave.

Yes, that’s extreme, and the thought of losing 25% of customers is usually enough to cause a small business owner to have a breakdown.

But let’s at least see what this might mean for Eddie’s profit:

That could double his profit and some! Surely worth exploring further.

But again, there’s a problem I hear. “I sell a commodity product and it can’t be differentiated” or “My service is a commodity and it’s the same as everyone else”.

You can differentiate anything

Here’s an important definition:

A commodity is a basic good used in commerce that is interchangeable with other commodities of the same type; commodities are most often used as inputs in the production of other goods or services.

The quality of a given commodity may differ slightly, but it is essentially uniform across producers.

Very often business owners think that definition describes their product or service and they fall into the commodity trap.

In other words, they believe what they sell is a commodity and therefore must compete on price. However, a product (or service) is only a commodity if you think it’s a commodity and you treat it like that.

Ultimately, with creative thinking, anything can be differentiated, and therefore sold at a higher price.

Take lettuce for example.

You can buy a whole lettuce for a certain price. How do you differentiate it? It’s just a lettuce.

We know customers want convenience. And many years ago, someone came up with the idea to cut up the lettuce, wash it and put it in a bag. It’s still the same lettuce. But people willingly pay significantly higher prices (over 100% higher) per kg of lettuce.

What about water?

Much of the earth is made up of water. It comes out of the kitchen tap and costs almost nothing. Surely, it’s a commodity.

Not if you differentiate it by putting it in a bottle, then you can sell it for much, much higher prices.

What about air?

Oxygen is the most abundant element on earth, so surely you can’t differentiate it and charge a price for it, let alone a higher price.

And yet companies like oxygenbars.com sell Personal Oxygen Dispensers for $29.99 each. It’s a thriving market.

The ultimate commodity

Arguably the ultimate commodity is stocks and shares. After all, a share in Disney is traded on stock exchanges around the world at the same price.

How can you differentiate the ultimate commodity, when at any point in time it’s the same price around the world?

The website GiveAShare.com does exactly that. You can buy a share in companies such as Disney, McDonalds and Harley Davidson for typically DOUBLE the price listed on a stock exchange. How?

Very simple. They differentiate it by putting it in a frame. You can choose the type of frame. Then you can add an engraved plaque. They’ve turned the product into something different; a gift. That opens up a new market for people who want to buy shares in iconic companies as a gift for a loved one.

If you can differentiate lettuce, water, air and shares, you can differentiate what you do.

So how can you make your product or service different? How can you make it better? How can you make it more convenient? How can you change the way you package your product to make it different? Later in this book we’ll look at how you can do this in more detail.

When you differentiate your product from the competition, customers will pay you higher prices.

Are you convinced?

If not, we’ll look at one of the biggest pricing myths in the next chapter.